There are few poets more renowned in the twentieth century than Gwendolyn Brooks. Her parents experienced a classic love story: her father was a janitor that gave up a life of prosperity as a doctor to raise a family, while her mother was a concert pianist and teacher.

Brooks herself was born on June 7, 1917, in Topeka, Kansas. She spent most of her life in Chicago, however, as the Great Migration took its toll on African-American families in the South and Midwest. As a youth, Brooks had a great deal of experience with the racism and segregation infesting the United States; two of the three schools she attended might have been integrated, but throughout her teenage years she faced racial injustices and prejudices that led to form the backbone of some of her more renowned poems.

In a way, she is the quintessential example of a Writer of the Week; she refused to complete a four-year program at Kenendy-King College simply due to the fact that she wanted to strike away as a writer.

Brooks’ career as a poet began at age thirteen, when she published her first poem in “America’s Childhood,” a nationally recognized children’s magazine. Part of her early success stemmed from several other well-known poets, such as Langston Hughes and Richard Wright, though it was clear even from an early age her poetic style set her apart from others.

The characters in her poetry took strong influence from the little apartment she lived in during her twenties, where she said she could “look first on one side and then on the other. There was my material.”

Brooks’ writing style catered to reality, as bleak and as beautiful as it could be in Chicago’s South Side. Richard Wright, one of the most respected African-American authors of the time, noted to one of her publishers that “she takes hold of reality as it is and renders it faithfully… she easily catches the problem of color prejudice among Negroes.”

Amongst all of her poems, she writes with an almost static punch, a burst of emotion that accompanies each word. Many pieces are short, easily scanned in a minute, but no matter if it’s ten lines or a hundred, Brooks manages to strike each syllable with an impact that refuses to bow to flowery prose or smooth transitions.

Brooks’ later life, when not focused on her poetry and teaching others about the impact writing can have, was dedicated largely to social activism. Her works, especially from the 1960s onward, contain a political undertone that one can’t help but recognize. Her poems, naturally, focus on the tribulations and the small victories of the urban African-American lower class, and her only novel stars an African-American woman surrounded by a patronizing and racist white society.

While recent studies suggest that Brooks had her hand in leftist politics for decades and developed a black nationalist stance to distance herself from any government connections, she is most often and fondly remembered for her work towards achieving her own victories in the fight for civil rights.

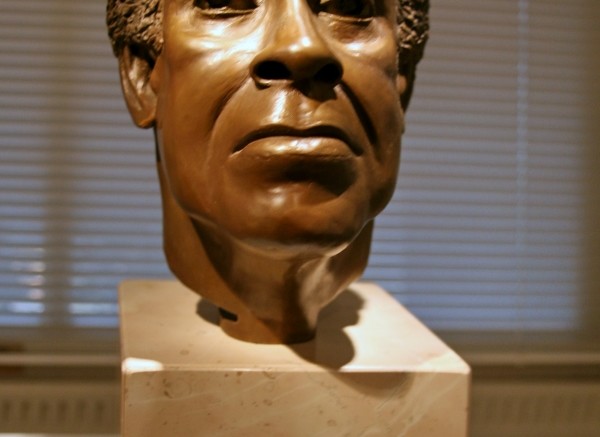

Brooks, for all her work and all her glory as an excellent poet, passed away in December of 2000. Her life has still been celebrated today; she is still recognized as the first African American to receive a Pulitzer Prize. While you can’t follow her on any social media, you can read more about her here and sample some of her poetry here.